Right now, we are talking to investors about ways to buy the dip. From the highs of December, it is pretty remarkable how quickly markets have reversed. Stocks were already down in January as fears of inflation and rising interest rates took hold. The war in Ukraine has shocked the world and we are seeing tragic consequences of this inexcusable aggression. Inflation was reported at 7.9% for February and that was before we saw gas prices surge in March following the Russia sanctions.

This past Tuesday, we saw 52-week lows in international stock funds, such as the Vanguard Developed Markets Index (VEA) and the Vanguard Emerging Markets Index (VWO). Here at home, the tech-heavy NASDAQ is down 20%, the threshold used to describe a Bear Market. It’s ugly and there’s not a lot of good news to report.

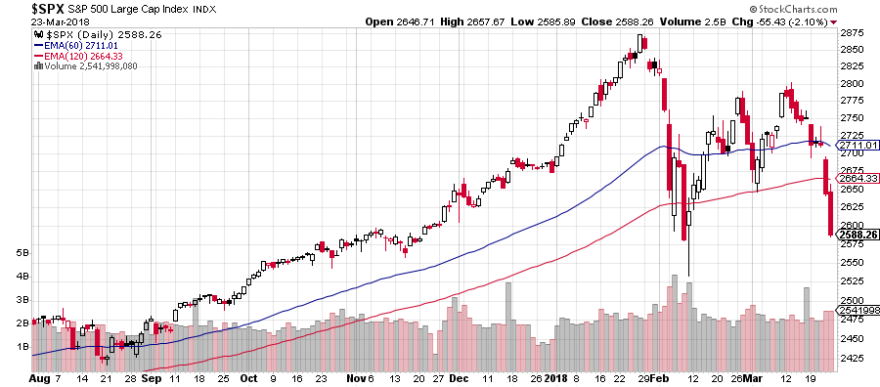

Ah, but volatility is the fundamental reality of investing. Volatility is inevitable and profits are never guaranteed. In December, when the market was at or near all-time highs, everyone was piling into stocks. And now that many ETFs are near their 52-week lows, investors are wondering if they should sell.

Market timing doesn’t work

Unfortunately, our natural instinct is to do what is wrong and want sell the 52-week low rather than buy. Back in December, there were a lot of people hoping for a correction to make purchases. Now that a correction is here, it’s not so easy to pull the trigger on making purchases. The risks seem heightened today and nobody wants to try to catch a falling knife. Unfortunately, the market isn’t going to tell us when the bottom is in place and it is “safe” to invest.

Last week was the 13-year anniversary of the 2009 Lows. Most reporters say that the low was on March 9, 2009, because that was the lowest close. But I remember being at my desk when we saw the Intraday low of 666 on the S&P 500 Index on 3/06/09. Today, the S&P 500 is at 4,200 (down from a recent 4,800). Even with the 2022 drop, we have had a tremendous run for 13 years, up 530%.

A prospective client asked me this week what I had learned from being an Advisor back in 2008-2009. And I told her: First, you can’t time the market. Clients who decided to ride out the bear market did better than those who changed course. Second, individual companies can go out of business. You are better off in diversified funds or ETFs rather than trying to pick stocks.

Buying The Dip

While you shouldn’t try to time the market, we do know that “buying the dip” has worked well in the past. Since 1960, if you had bought the S&P 500 Index each time it had a 10% dip, you would have been up 12 months later 81% of the time. And you would have had an average gain of 12%. That’s a pretty good track record.

I feel especially confident about buying index funds on a dip. While some companies will inevitably become smaller or go out of business, an index like the S&P 500 holds hundreds of stocks. Over time, an index adds emerging leaders and drops companies on their way down. That turnover and diversification are an important part of managing an investment portfolio.

So with the caveat of buying funds, what are ways to buy the dip today? What if you don’t have a lot of cash on the sidelines? After all, if we don’t time the market, we are likely fully invested at all times already.

5 Purchase Strategies

- Continue to Dollar Cost Average. If you participate in a 401(k), keep making your contributions and buying shares of high quality, low cost funds. If you are a young investor, you should love these market drops. You can accumulate shares while they are on sale!

- Make your IRA contributions now. If you make annual contributions to an Traditional IRA, Roth IRA, 529 Plan, or other investment account, I would not hesitate to proceed. Make your contribution when the market is down.

- Rebalance your portfolio. Do you have a target allocation, such as 70% stocks and 30% bonds? With the recent volatility, you may have shifted away from your desired allocation. If your stocks are down from 70% to 65%, sell some bonds and bring your stock level back to 70%. Rebalancing is a process of buying low and selling high.

- Limit orders. If you do have cash, you could dollar cost average. Or, with your ETFs you can use limit orders to buy at specific prices.

- Sell Puts. Rather than just use limit orders, I prefer to sell Puts for my clients. This is an options strategy where you get paid for your willingness to buy an ETF at a lower price. We have been doing this for larger accounts with cash to deploy, but this not something most investors would want to try on their own.

Uncertainty, Risk, and Sticking to the Plan

There is always risk as an investor. Whenever you buy, there is a possibility that you will be down and have a loss in a week, a month, or a year from now. Luckily, history has shown us that the longer we wait, the better chance of a positive return in a market allocation. We have to learn to accept volatility and be okay with holding during drops.

We can go one step further and seek ways to buy the dip. To me, Risk means opportunity, not just danger. So, which is riskier, buying at a 52-week high or at a 52-week low? Well, neither is a guarantee of success, but given a choice, I would rather buy at a low. And that is where we are today.

I think back to March of 2020, when the market crashed from the COVID shut-downs. And I recall the horrible markets in March of 2009. In both cases, we stuck to the plan. We held our funds and didn’t sell. We rebalanced and made new purchases with available funds. That is what I have been doing with my own portfolio this month and it’s what I have been recommending to clients. We don’t have a crystal ball to predict the future. But we do know what behavior was beneficial in the past. And that is the playbook I think we should follow.

Amazingly, I have had only a couple of calls and emails from clients concerned about the market. None have bailed. We are in it for the long-haul. Market dips are inevitable. It is smarter to ignore them than to panic and sell. And if we can make additional purchases during market dips, even better.

Past performance is no guarantee of future results. Investing includes risk of loss of principal and Dollar Cost Averaging may not protect you from declining prices or risk of loss.